In the evolving landscape of biostatistics consulting and collaboration within universities and academic medical centers, the financial models underpinning these units are diverse and multifaceted, reflecting the varying priorities, resources, and structures of each institution. These funding frameworks may include centralized budget allocations from the institution, direct grant funding from specific research projects, or a service model where biostatisticians charge fees for their time and expertise.1,2

Each funding structure uniquely shapes the way biostatisticians engage with research teams. For instance, institutions with centralized funding might prioritize long-term strategic partnerships, allowing biostatisticians to engage more fully in project planning, study design, and methodological innovation. In contrast, a fee-for-service model may emphasize efficiency and volume, encouraging biostatisticians to focus on discrete tasks or quick consultations. Meanwhile, grant-funded roles often involve deep collaboration on specific projects, with biostatisticians embedded within research teams and closely aligned with the project’s scientific goals.

The type of funding also influences the efficiency of biostatistical support. Centralized funding might enable greater availability and responsiveness, while fee-for-service models may require researchers to allocate funds carefully, potentially limiting access for projects with smaller budgets. Additionally, grant-funded models can create pressures related to project timelines and resource allocation, as biostatisticians balance multiple project commitments.

Ultimately, the financial structures that support collaborative biostatisticians play a critical role in determining their capacity to contribute meaningfully to research, impacting everything from project outcomes to the broader institution’s research productivity and innovation. These models not only shape the day-to-day activities of biostatisticians but also affect their potential for professional development, long-term engagement in institutional research agendas, and capacity for methodological advancement within the academic community.

Sections

The Landscape of Biostatistics Funding Models

Collaborative biostatisticians often find themselves in positions funded through a variety of mechanisms. In some cases, these positions are entirely funded by institutional-level sources, allowing unrestricted access for researchers across the institution. More commonly, however, funding is project-based, tied to specific grants or contracts, which can create challenges for biostatisticians.

When collaborative biostatisticians have 100% of their time allocated to specific research projects, they face several hurdles. First, their responsibilities may include administrative tasks, performance evaluations, and professional development, which often go neglected due to time constraints. Moreover, opportunities for method development or personal research projects are limited, leading to potential career dissatisfaction and attrition as biostatisticians seek more flexible roles that afford them greater autonomy.3

The funding model not only affects individual biostatisticians but also impacts the collaborative unit as a whole. If all biostatisticians are fully funded through existing grants, the unit may struggle to initiate new projects due to a lack of available personnel. This situation necessitates a shift towards a more flexible funding approach that allows biostatisticians the time needed for professional growth, leadership, and process improvement.

Understanding the Hourly Billing Model

In many consulting scenarios, the traditional hourly billing model prevails, wherein clients pay based on the number of hours spent on a project. While this model allows for straightforward billing, it can foster a transactional relationship, viewing biostatisticians as hired hands rather than integral team members.

The Challenges of Hourly Billing

-

Transactional Nature: Hourly billing emphasizes the hours worked rather than fostering a collaborative partnership, limiting the potential for strategic input from biostatisticians.

-

Lack of Incentives: Biostatisticians may feel constrained to only fulfill immediate project requirements, which can stifle creativity and limit engagement in broader discussions or exploratory projects.

-

Scope Creep Concerns: Clients may hesitate to engage in broader conversations or exploratory work due to fear of accruing additional charges, restricting innovative solutions.

The Alternative: FTE Billing

In contrast, Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) billing represents a transformative shift in how biostatistics consulting services are perceived and structured. This approach entails clients paying for a dedicated biostatistician or team on a monthly or annual basis, leading to several key benefits:

-

Enhanced Collaboration: FTE billing encourages a partnership mentality between the biostatistics unit and its clients. When clients have access to dedicated biostatistical support, they are more likely to integrate biostatisticians into the research process as valuable collaborators rather than external service providers.

-

Predictable Costs: By moving away from the unpredictable nature of hourly billing, FTE billing allows for more accurate budget planning and financial management. Clients can allocate funds more effectively, knowing the costs associated with dedicated biostatistical support.

-

Focus on Outcomes: FTE billing shifts the focus from merely tracking hours to achieving project outcomes. Biostatisticians are incentivized to work efficiently and effectively, as their success is linked to the overall success of the research projects.

The Case for Flexible Funding

Within the FTE framework, flexible funding is defined as any funding not directly linked to a specific research project.4 Allocating 10% to 20% of a biostatistician’s time to flexible funding can mitigate the challenges associated with project-based funding. This reserved time can be utilized for essential tasks such as administrative duties, mentorship, and professional development (related to funded projects or otherwise). In certain cases, especially for new hires, allocating a full 100% of their time to flexible funding during onboarding may be beneficial. This approach not only facilitates their training but also helps maintain the operational capacity of the collaborative unit during staffing transitions.

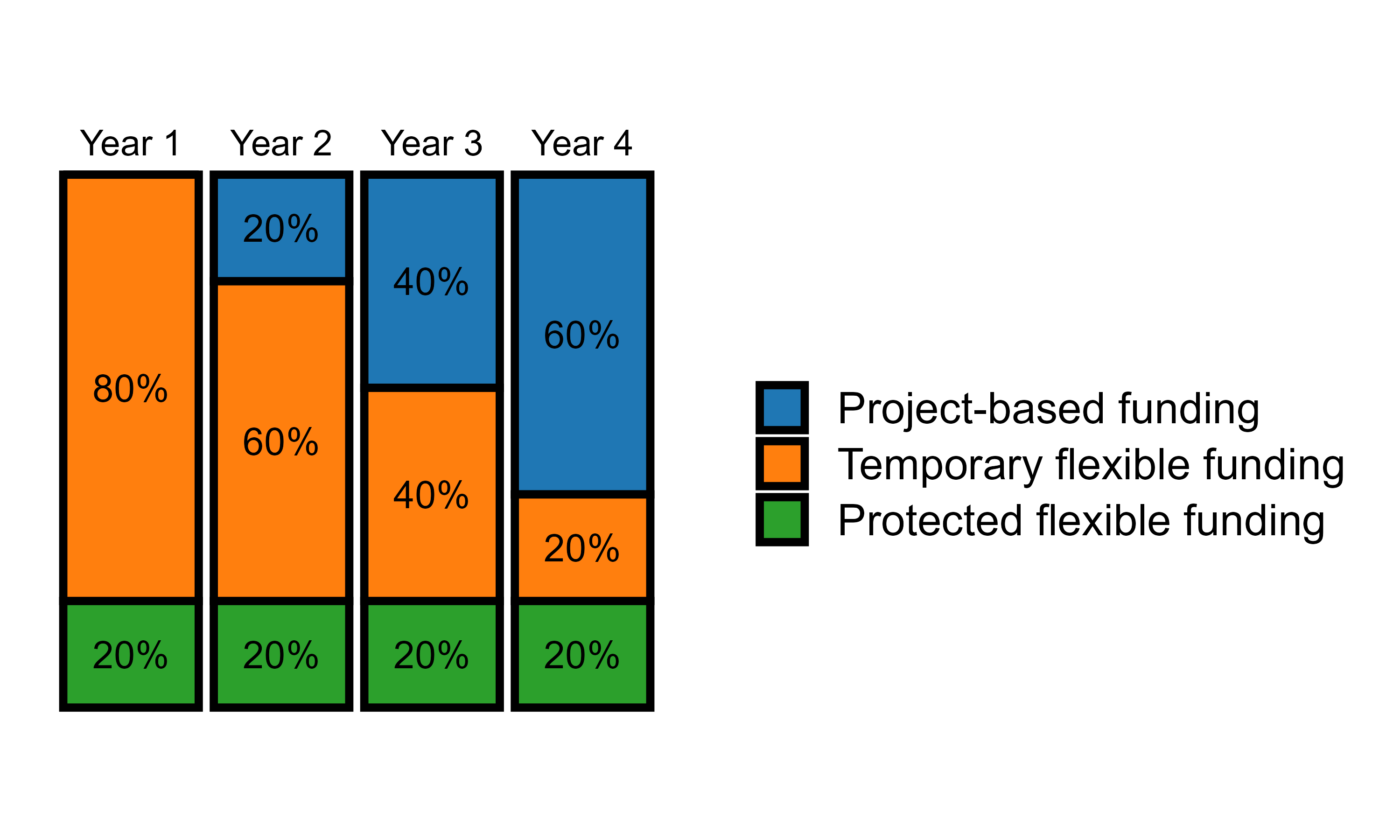

A graduated flexible funding allocation strategy enhances unit growth and stability, signaling when to hire new staff based on project-based funding levels.4 For instance, when a biostatistician’s project-based funding reaches 50-60% (i.e., 0.5 Full-Time Equivalent; FTE), it may be an appropriate time to initiate recruitment for a new position (Year 4 in this illustration).

Adapted from Slade, et al. (2024) 4

Adapted from Slade, et al. (2024) 4

In queueing theory (or line waiting theory), the primary goal is to optimize systems where waiting lines or queues form, such as customer support, IT service desks, or any process involving service requests such as an intake form for biostatistical support.5 To reduce wait times, it’s essential to ensure that the system has sufficient capacity to handle incoming requests promptly.

Allocating 10-20% of a person’s time as untaken (unassigned to specific tasks) can significantly reduce the queue wait time for the following reasons:

1. Handling Random Arrivals (Variability)

- In most biostatistical support intake systems, the arrival of projects or requests is not perfectly predictable. Requests can arrive in bursts (e.g., conference or grant cycles) or be unevenly spaced throughout the year.

- Having 10-20% of employee time as unassigned helps absorb this variability. When a sudden increase in demand occurs (more requests than usual), employees can use their untaken time to immediately respond to new tasks, reducing the overall queue and wait time.

2. Reduced Service Delays

- Staff who are fully booked with tasks and have no extra capacity will not be able to address new requests until they finish their scheduled work.

- By leaving a buffer of 10-20% of time untaken, employees can begin handling new tasks sooner. This reduces the service delay (the time between when a task is requested and when it is started), resulting in shorter wait times for customers.

3. Minimizing the Impact of Variability in Service Time

- The time it takes to complete each task (service time) also varies. Some requests may take much longer than others.

- With some untaken time, employees can compensate for these longer tasks by adjusting their workload dynamically, preventing queues from building up when tasks take longer than expected.

4. Increased System Responsiveness

- Queueing systems that operate at or near 100% capacity (where employees are fully booked all the time) tend to experience longer wait times and delays because there is no room to handle sudden surges in demand.

- Keeping 10-20% of employee time untaken allows for quicker responses to new tasks, as employees have time available to jump in without being constrained by a fully booked schedule. This flexibility improves the overall responsiveness of the system, keeping the queue shorter.

5. Avoiding Overload and Saturation

- In queueing systems, the closer the employee’s capacity is to being fully utilized, the higher the risk of overload. Once the system is overloaded, queues grow exponentially.

- The 10-20% untaken time acts as a buffer, reducing the risk of saturation and helping the system stay in a more manageable, stable state where wait times are kept lower.

Try the Wait-time Calculator

You can use the interactive tool below to estimate your wait time to start a new project based on your workload, percent of flex time, and the priority level for the new intake:

Conclusion

The financial models underpinning biostatistics consulting and collaboration are critical to shaping the effectiveness and satisfaction of biostatisticians in research support settings. By transitioning from hourly billing to a more collaborative FTE model and incorporating flexible funding structures, institutions can enhance the collaboration, productivity, and innovation of their biostatistics units. This paradigm shift not only benefits individual biostatisticians by affording them time for unexpected complications on a project, professional development and leadership but also strengthens the overall research capacity of the institution, ultimately advancing scientific inquiry and improving health outcomes.

References

- Sharp, J., Griffith, E. H., Craig, B. A., Hanlon, A., Peskoe, S., & Van Mullekom, J. (2024). The current landscape of academic statistical and data science collaboration units with examples. Stat, 13(3), e718.↑

- Hanlon, A. L., Lozano, A. J., Prakash, S., Bezar, E. B., Ambrosius, W. T., Brock, G., ... & Pomann, G. M. (2022). A comprehensive survey of collaborative biostatistics units in academic health centers. Stat, 11(1), e521.↑

- Welty, L. J., Carter, R. E., Finkelstein, D. M., Harrell Jr, F. E., Lindsell, C. J., Macaluso, M., ... & Ware, J. H. (2013). Strategies for developing biostatistics resources in an academic health center. Academic Medicine, 88(4), 454-460.↑

- Slade, E., Robbins, S. J. K., McQuerry, K. J., & Mangino, A. A. (2024). The value of flexible funding for collaborative biostatistics units in universities and academic medical centres. Stat, 13(2), e679.↑

- Gross, D., Shortle, J. F., Thompson, J. M., & Harris, C. M. (2011). Fundamentals of queueing theory (Vol. 627). John wiley & sons.↑